Memphis International Airport in the early 1970s. Photo courtesy of Ed Uthman/Wikimedia Commons

In the very early days of commercial aviation, designers used train stations as inspiration for airport terminals. But the unique demands of the industry eventually led to a departure from the train station template. Individual hold rooms distributed along concourses replaced marshalling passengers from large, central waiting rooms as the norm. This increased the horizontal spread of the facility which, at larger airports, led to the adoption of various mechanical means of conveyance to shorten the travel times and distances for passengers. These systems de-coupled the adjacency demands of aircraft boarding from those of ticketing and baggage claim with resulting impacts on terminal design. This, more than any other factor, has influenced the horizontal layout of the terminal building. But what about the vertical?

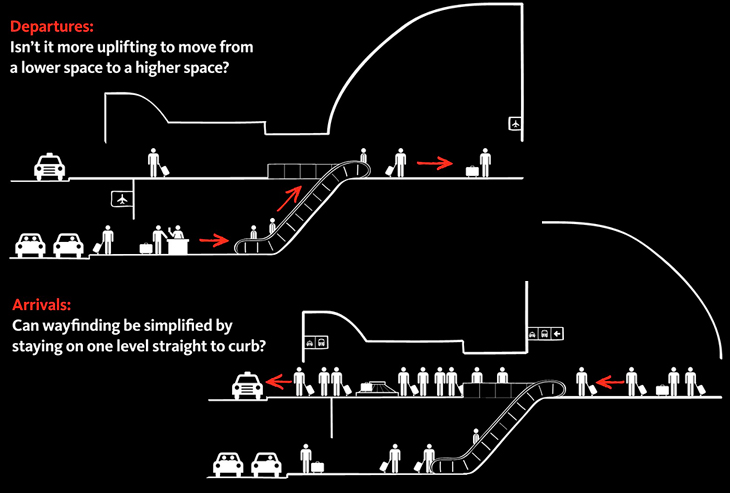

Image courtesy of Gensler

While greater curb frontage requirements initially drove the need for a two-level terminal, the vertical design of terminals remains trapped by the legacy of the 1960s in ways that that no longer make sense. Consider the vertical stacking of nearly all airport terminals in the world. Ticketing sits atop baggage claim. Sometimes interstitial levels such as mezzanines or basements exist in between, but the ticketing/baggage vertical relationship remains unchanged. Why is this so, and is this template still relevant?

Before answering this question, it’s important to remember that in the first airport terminals, two design factors loomed large.

Atlanta Municipal Airport circa 1956. This was the world's longest ticket counter when the terminal opened in 1948. Photo courtesy of Life Magazine Photo Archive

First, the airlines viewed the terminal as the point-of-sale, while baggage handling was relatively simple and gravity-based. Since airlines drove design decisions, the ticketing level functioned as the marquee space in the terminal, with high ceilings, lots of natural light, and large windows providing views to the airline-branded interiors. Airlines fought to be located first on the entry roadway so they were more visible and could provide easier access to their passengers.

The ticketing area at the Gensler-designed John Wayne Airport in Orange County, California. Photo courtesy of Gensler

None of these concerns are relevant today. Ticketing and check-in can be done either at home or at machines located throughout terminals. Where possible, passengers avoid the ticket lobby and head first for the security checkpoint. If ticketing no longer holds much significance, why does the ticketing lobby still dominate the architecture?

Second, baggage systems used to be quite simple. Passengers dropped their bags at the counter on the upper level, where the agent could put it on a slide or a simple conveyor that would take it down to the carts on the ramp. Baggage claim sat on the ramp level so the carts with the arriving bags could just pull up to a shelf or a racetrack device and offload directly. Thus ticketing lobbies sat above and baggage claim below.

But as terminals grew in size and the number of bags increased, airports could not scale this simple system. More sophisticated baggage conveying systems that decoupled the adjacency between the baggage cart and the baggage claim area became standard. Increased volumes of bags and the number of destinations meant larger, more complex baggage sorting areas that had to be located remotely from the check-in hall. Both of these advances eliminated any real necessity for the check-in and baggage claim to be located in a rigid horizontal or vertical relationship with the baggage carts on the ramp.

Fast forward to today. The idea of celebrating ticketing and check-in as the beginning of a journey is now anachronism. The arrival of a passenger to a community is the most significant moment in travel today, but airports continue to send arriving passengers down to a cramped, dark space on floors that sit below underutilized ticketing counters.

Baggage claim area at Baltimore Washington International Airport. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Isn’t it time we reversed this model? Shouldn’t the airport welcome arriving passengers and visitors with a celebratory experience in a spacious, naturally illuminated space on a terminal’s upper level? Can’t those increasingly few who need to check bags be accommodated on the floor below?

The only real constraint to inverting conventional terminal design is existing roadway systems. In airports with multiple terminals served by a common roadway system, such as LAX, the signage and directional challenges make this an inappropriate solution. At unit terminals with independent roadway systems, however, there is no practical reason why a baggage claim up, ticketing down arrangement wouldn’t work just as well. In Tulsa, for example, the terminal has this basic vertical organization and is well regarded.

We think that in the right situation, the flipped terminal can better serve the community and enhance the passenger experience. There are no additional costs or functional Kryptonite. The only real constraint is the inertia of conventional thinking.

Read more about our Terminal 2020 model in Dialogue.

|

Keith Thompson lives and breathes airport design. A leader of Gensler’s global aviation & transportation practice, he leads design teams to build award-winning airports around the globe. Contact him at keith_thompson@gensler.com. |